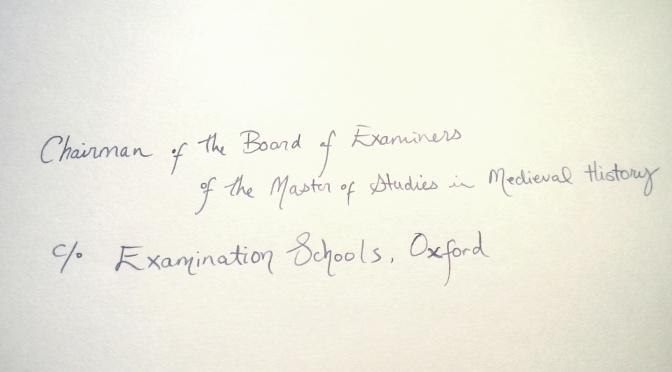

At long last, Friday was dissertation submission day, and as I threw open the curtains I was delighted to find that Oxford had graciously decked herself out for the occasion in her best blue skies and sunshine. My own dissertation copies had been bound at the print shop on Holywell Street the afternoon before and had been sitting in their envelope addressed to the

Chairman of the Board of Examiners

of the Master of Studies in Medieval History

c/o Examination Schools

High Street

Oxford,

on my desk all evening, forcing me to resist the temptation to flip through them one more time to discover each typo that had inevitably made it past a dozen rounds of proofreading.

Unlike the last time we submitted at the Exam Schools, an August submission day is a relatively anticlimactic affair. Unsure of when others planned to submit, I just walked into the nearly empty Schools on the way into town, filled out my submission slip, and handed it to the lone woman behind the desk. As I walked out, my little yellow receipt was the only evidence that I had, in fact, just completed an Oxford master’s degree.

I found the rest of my classmates camped out in the upper sitting room of the Turl Street Kitchen, addressing envelopes and waiting to collect their various oeuvres from the binders.

‘You look very relaxed!’ was my welcome.

I waived my yellow slip triumphantly, bringing down a kindly stream of curses upon my head.

After a stop at the binders, we then processed back to the Schools, assuring each other along the way that it was fine, that we were fine, that it was all going to be all right. A picture on the steps with dissertations in hand, and then two minutes later we were all out again, suddenly feeling strangely bereft.

A celebration was called for, however, and we decided on true Oxford tradition: a picnic of the finest drinks and comestibles that Tesco had on offer, partaken in the dappled shade of Christ Church Meadow. A few of us tried to ban all talk of anything occurring before the 1950s, but that didn’t prevent a long discussion on popes, bawdy comments about monks, and a discursive on ancient college feuds.

Our attempts at punting then being stymied by the previous night’s rain, which had irremediably waterlogged our prospective crafts, we settled into lawn chairs in the garden of Balliol’s Holywell Manor, mixing slumber with desultory conversation on such things as colleges and croquet, letting the stress of the past eleven months slowly drift away with the breeze.